The Colorado Potato Beetle

The Colorado Potato Beetle is my arch nemesis in the garden. I have not so fond memories of spending childhood days in the garden picking off the beetles and squishing the larvae. It was summer break! I had better things to be doing like fishing or shooting pop cans with my slingshot.

Today, I look at the Colorado Potato Beetle with the same disdain. A few weeks, on a Tuesday evening, ago I saw one on my beautiful row of Yukon Gold potatoes. Crushing it under my boot, I thought, “Well, I had better do something about that this weekend.” That Friday, I stopped by our market to get a bottle of Colorado Potato Beetle Beater by Bonide. The next morning I found total carnage in my garden. That one beetle had become an invasion! How could this happen so quickly!?

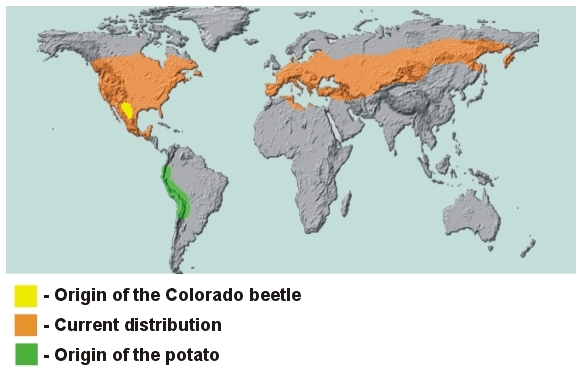

The Colorado Potato Beetle is a good example of what happens when people move plants and animals out of their natural habitat. Potatoes are not the natural food source for the beetle. The beetle is a native of western North America and potatoes originated in South America. The beetle was discovered in 1824 by Thomas Say from specimens collected in the Rocky Mountains on buffalo-bur, the beetle’s natural food of choice. The origin of the beetle is somewhat unclear, but it seems that Colorado and Mexico are a part of its native distribution in southwestern North America. In about 1840, the species adopted the cultivated potato into its host range and it rapidly became a most destructive pest of potato crops.

In 1877, the Colorado beetle reached Germany where it was eradicated. During or immediately following WWI, it became established near USA military bases in Bordeaux and proceeded to spread by the beginning of WWII to Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain. The population increased dramatically during and immediately following WWII and spread eastward, and the beetle is now found over much of the continent.

Colorado potato beetle females are very prolific; they can lay as many as 800 eggs. The eggs are yellow to orange, and are about 1 mm long. They are usually deposited in batches of about 30 on the underside of host leaves. Development of all life stages depends on temperature. After 4–15 days, the eggs hatch into reddish-brown larvae with humped backs and two rows of dark brown spots on either side. They feed on the leaves. Larvae progress through four distinct growth stages (instars). First instars are about 1.5 mm long; the fourth is about 8 millimeters (0.31 in) long. The larvae in the accompanying picture are third instars. The first through third instars each last about 2–3 days; the fourth, 4–7 days. Upon reaching full size, each fourth instar spends an additional several days as a non-feeding prepupa, which can be recognized by its inactivity and lighter coloration. The prepupae drop to the soil and burrow to a depth of several inches, then pupate. Depending on temperature, light-regime and host quality, the adults may emerge in a few weeks to continue the life cycle, or enter diapause and delay emergence until spring. They then return to their host plant to mate and feed. In some locations, three or more generations may occur each growing season.

The beetles are a serious pest of potatoes; however, they may also cause significant damage to tomatoes and eggplants. Both adults and larvae feed on foliage and may skeletonize the crop. Insecticides are currently the main method of beetle control on commercial farms. However, many chemicals are often unsuccessful when used against this pest because of the beetle's ability to rapidly develop insecticide resistance. The Colorado potato beetle has developed resistance to all major insecticide classes, although not every population is resistant to every chemical.

In our region Colorado Potato Beetles still seems to be susceptible to treatment with spinosad-based insecticides. Spinosad is an insecticide based on chemical compounds found in the bacterial species Saccharopolyspora spinosa. It was first registered as a pesticide in the United States for use on crops in 1997. It is regarded as natural product-based, and approved for use in organic agriculture.

If you want to totally avoid the use of pesticides in your garden, your treatment options are limited to the method that I despised as a child. Pull the adult bugs off by hand and place them in a jar of water to drown. Then, with the larvae, things get messy. Simply pinch them to kill them. Their guts will shoot out their butts. (I had pretty good aim as a youngster!) As a bonus, your now dead jar of adult beetles makes for some great fishing bait. Bluegill love them!

The Colorado Potato Beetle is a problem that we have had to deal with for well over a century. I guess that’s kind of comforting when facing their destruction in your own garden. You’re not alone in this battle.

Fun Fact: During the Cold War the Warsaw Pact countries, fearing a food shortage, decried the beetle as a CIA plot to destroy the agriculture of the Soviet Union. Officials launched a Warsaw Pact-wide campaign to wipe out the beetle, villainizing them in propaganda posters. In East Germany they were known as Amikäfer (Yankee beetles).