The Gardens at Mount Vernon

George Washington oversaw all aspects of the landscape at Mount Vernon. He extensively redesigned the grounds surrounding his home, adopting the less formal, more naturalistic style of 18th century English garden landscape designer Batty Langley. Washington reshaped walks, roads, and lawns; cut vistas through the forest, and planted hundreds of native trees and shrubs. The well-ordered gardens provided food for the Mansion's table and were also pleasing to the eye. Eighteenth-century visitors to Mount Vernon were delighted by bountiful offerings of fresh vegetables and fruits, and reveled in after-dinner walks amongst all manner of opulent flowering plants.

Washington loved his gardens and was constantly changing the plants used at Mount Vernon. There is little evidence to suggest, however, that he was the one gardening. There were many gardeners who worked at Mount Vernon, several of whom were indentured servants and slaves. For example, letters written from Washington to his estate manager, Lund Washington, and to John Washington, an acquaintance from King George City, Virginia, reveal that Philip Bateman served as the primary gardener at Mount Vernon between 1773 and 1785.

Washington created an ornamental landscape or "pleasure grounds" for the enjoyment of visitors and residents of Mount Vernon. At the center of the design is a large, guitar-shaped bowling green surrounded by a broad, serpentine gravel path to guide visitors as they meandered through the pleasure grounds. The highlight of any tour was the upper garden, which opened off the bowling green. From 1763 to 1785, the space served as a fruit and nut garden, but when Washington redesigned the space in 1785 he planted flowers within the enclosure. A pleasure garden was a must-have for any genteel estate, but Washington would not allow too much precious space be expended on ornamental plants without a practical purpose. He followed the advice in an 18th-century gardening dictionary suggesting that if you did not have the acreage, you could combine pleasure with necessity. The flowers in the upper garden were planted in the border that surrounded the vegetable beds. Benjamin Latrobe wrote in his diary in 1796, "On one side of this lawn is a plain Kitchen garden, on the other a neat flower garden laid out in squares, and boxed with great precision." Walking the garden paths, one visitor wrote that they saw a "great variety of plants and flowers, wonderful in appearance, exquisite in their perfume and delightful to the eye..."

With a change of landscape coming and the addition of flowers in the upper garden, Washington was intent on adding a special structure to this particular garden: a greenhouse. He had admired Mrs. Margaret Tilghman Carroll's greenhouse at her home, Mount Clare, near Baltimore, and requested information for his construction. She not only shared information about her structure but also plants from her collection. Washington was thrilled and accepted her offer of plants, for he had recently hired a gardener "who professes a knowledge in the culture of rare plants and care of a green-house." The greenhouse kept tropical plants warm in the winter and served as a gallery of plants for the delight of Washington's guests. In the spring, the gardeners moved the plants out into the upper garden for the duration of their growing season. One guest wrote in 1799, "I saw there English grapes, oranges, limes and lemons in great perfection as well as a great variety of plants and flowers, wonderful in appearance, exquisite in their perfume and delightful to the eye..."

Martha Washington once wrote that vegetables "were the best part of living in the country." This produce was raised primarily in the kitchen garden. In the 18th century, every home outside the city had a vegetable or kitchen garden as these plots were necessary to supplement the diets of their inhabitants. In addition to the kitchen garden, the cultivated fields and every garden except the botanical garden contained vegetables. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington encouraged his troops to eat vegetables and even to plant them if time allowed. As one 18th-century horticulturist said, "A Kitchen-garden may be said to be the most useful and consequential part of gardening." Mount Vernon's kitchen garden has the distinction of never changing in its purpose. Since 1760, the kitchen garden has been cultivated continuously for the production of vegetables, and it still is today.

Manure, compost or dung was considered necessary to all soils. It was the salvation for soils robbed of their fertility and viewed as a material to improve all plants. In April 14, 1760, Washington described in his diary an experiment to determine the best compost for plants. He set up a box with 10 apartments, each containing 3 peaks of earth from the farm. The first box was the control, and to the others he added equal amounts of compost, dung, or mud from the creek, which he referred to as "Black Mould." In each division, three grains of wheat, oats and barley were planted at equal distance and depth. The results from the experiment showed that the best compost was the hardest to come by—the Black Creek Mould. Of all the dungs, horse manure was considered the best, but dung from cow, oxen, hog and sheep all had their good qualities and were suggested for use. There was a warning about pigeon and chicken manure because it was very hot and could burn plants. When it was to be used, it was suggested to use half as much of that material than the others. Depending on the use, manures could be used fresh but very often the manures, even human, were meant to go through a heat or decomposition of upwards to a fortnight or two weeks before it was used. Washington's interest in manures and compost and their importance is obvious in a letter he penned to his friend George William Fairfax requesting that he find Washington a farm manager: "above all, Midas like, one who can convert everything he touches into manure, as the first transmutation towards Gold."

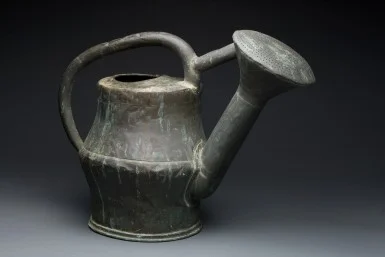

Garden tools have not changed much from the eighteenth century, but they were as critical to a gardener then as they are now. In Elysium Britannicum, prolific writer John Evelyn (1620–1706) wrote about the practice of gardening sketched the tools of the trade. Evelyn declared, "Gardining ... hath as all other Arts and Professions certaine Instuments and tooles properly belonging to it." The three most important garden tools were the spade, the shovel and the rake. The spade was used for turning the ground and making it smooth, the shovel for throwing earth out of trenches and ditches, and the rake for keeping the garden tidy. Another critical implement was the pruning knife, as it was said that there are, "a hundred occasions in the way of Gardening to make use of it." Other gardening tools that would have been found in the gardeners' tool house at Mount Vernon were garden shears, long pruners, baskets, water cans, pick axes, a ladder, and a stone roller. There are frequent mentions in Washington's gardeners' weekly reports to raking and rolling the garden paths. In Le Jardinier Solitaire, by François Gentil & Louis Liger (1706), the authors wrote, "As a Soldier can't fight without his Arms, so a Gardner can't work without proper Tools. The one is as necessary as the other."